|

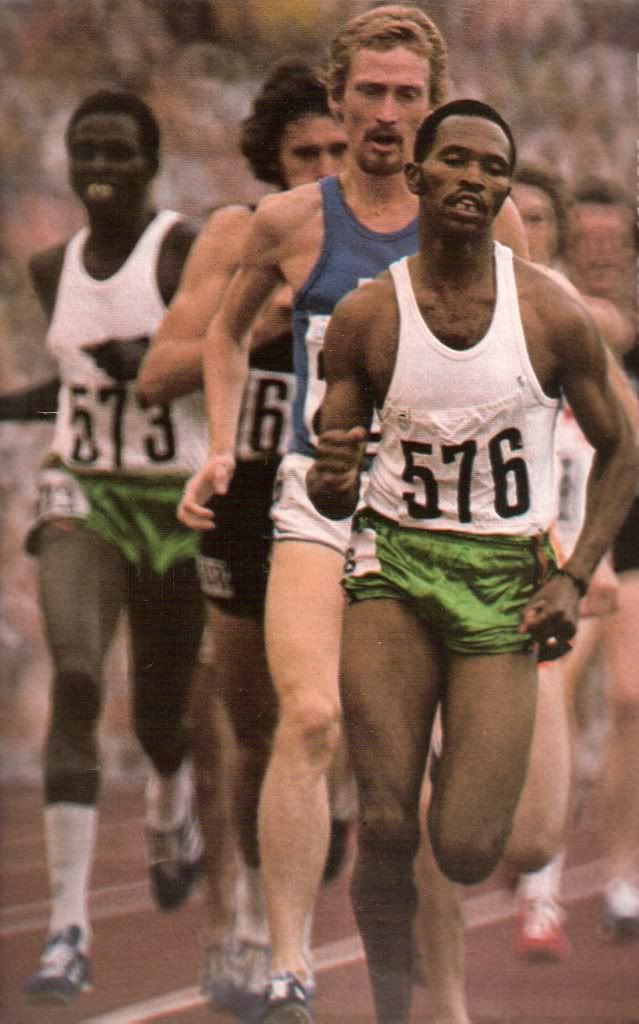

| Mohamed Kedir leads Lasse Viren at the Moscow Olympics 10.000m final http://www.elatleta.com/ |

At the start line of the Moscow Olympic male 10.000m there were two equally outstanding favourites but with rather different athletic résumé prior to the 1980 Games. Lasse Viren, the last of the flying Finns, had achieved the “double double”: he had become the first man in winning the 5000m and 10.000m titles in two consecutive Olympic Games, Munich and Montreal. After having won everything, Viren was still going strong and aimed in

|

| Miruts Yifter, Tolossa Kotu and Kaarlo Maaninka at Moscow Olympics http://www.elatleta.com/ |

Historically, Finland Stockholm Finland Finland Finland

Lasse Viren’s personality had been formed in the small village of Myrskyla Brasil , Colombia , Kenya

Hard work and focus paid off. Viren arrived to the Olympic dates of Munich and Montreal Munich , there was an unforgettable day for Finland New Zealand

|

| Kipchoge Keino leads Pekka Vasala at the 1500m at Munich Olympics http://www.elatleta.com/foro/showthread.php?136398-El-grado-cero./page2 |

|

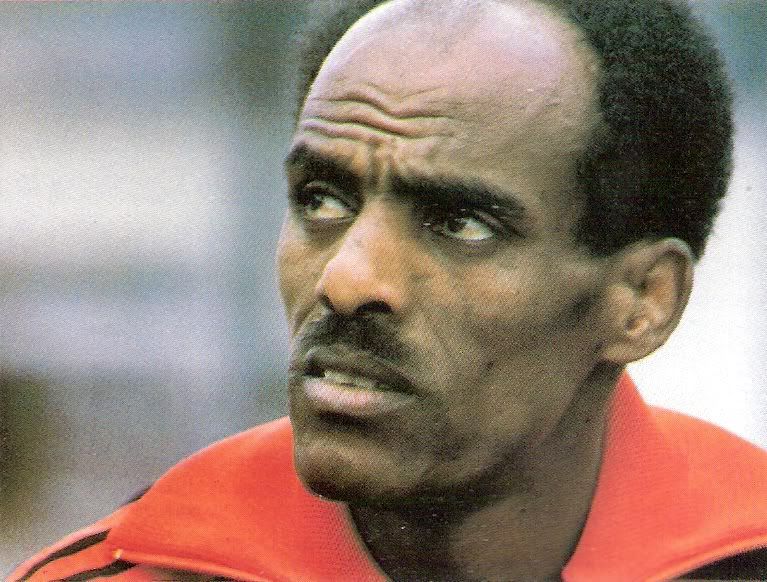

| Miruts Yifter, double Olympic champion in Moscow http://www.elatleta.com/foro/showthread.php?136398-El-grado-cero. |

1

|

Miruts

|

Yifter

|

15-may-44

|

ETH

|

27:42.69

| |

2

|

Kaarlo

|

Maaninka

|

25-dic-53

|

FIN

|

27:44.28

| |

3

|

Mohamed

|

Kedir

|

18-sep-54

|

ETH

|

27:44.64

| |

4

|

Tolossa

|

Kotu

|

15-mar-50

|

ETH

|

27:46.47

| |

5

|

Lasse

|

Virén

|

22-jul-49

|

FIN

|

27:50.46

| |

6

|

Jorg

|

Peter

|

23-oct-55

|

GDR

|

28:05.53

| |

7

|

Werner

|

Schildhauer

|

5-jun-59

|

GDR

|

28:10.91

| |

8

|

Enn

|

Sellik

|

10-dic-54

|

URS

|

28:13.72

| |

9

|

Bill

|

Scott

|

8-feb-52

|

AUS

|

28:15.08

| |

10

|

Ilie

|

Floroiu

|

29-nov-52

|

ROU

|

28:16.25

| |

11

|

Brendan

|

Foster

|

12-ene-48

|

GBR

|

28:22.54

| |

12

|

Mike

|

McLeod

|

25-ene-52

|

GBR

|

28:40.78

| |

13

|

Martti

|

Vainio

|

30-dic-50

|

FIN

|

28:46.22

| |

14

|

Gerard

|

Tebroke

|

9-nov-49

|

NED

|

28:50.08

| |

15

|

Antonio

|

Prieto

|

11-ene-58

|

ESP

|

DNF

|

Lasse Viren was an athlete with really economic running ways. Even someone with such floating style as 10.000m silver medallist in Munich Emiel Puttemans was quoted to feel irritated because his rival did not seem to make any effort while running. Furthermore, the last of the Flying Finns knew how to be in control of every race spending as less energy as possible. Viren’s world record at the 2 miles event some weeks before the Olympics, made enter the hopeful Finnish as the dark horse for the long distance races in Munich Bedford Bedford

In Montreal, at the 10.000m, things were even easier for Viren, because world cross champion Carlos Lopes did all the front running, steadily increasing his pace (the second half was run in a stunning negative split of 13:36.23). Everybody was left out by the brave Portuguese, except the same Viren, who did not have any problem in getting the better of a rival without final kick. In the 5000m final no one wanted to facilitate the Finn's victory this time, but the defending champion himself took the lead in the last stages of the race, running the last 1500m in a time which would have gained him the fourth place in the Olympic race won by John Walker, and again surging with 600m to go to eliminate the kickers as Kiwis Rod Dixon and Dick Quax. The unprecedented "double doble" at the Olympic long distance events had been done and Viren still had the strenght to achieve a praiseworthy 5th place at the marathon. (4)

In Montreal, at the 10.000m, things were even easier for Viren, because world cross champion Carlos Lopes did all the front running, steadily increasing his pace (the second half was run in a stunning negative split of 13:36.23). Everybody was left out by the brave Portuguese, except the same Viren, who did not have any problem in getting the better of a rival without final kick. In the 5000m final no one wanted to facilitate the Finn's victory this time, but the defending champion himself took the lead in the last stages of the race, running the last 1500m in a time which would have gained him the fourth place in the Olympic race won by John Walker, and again surging with 600m to go to eliminate the kickers as Kiwis Rod Dixon and Dick Quax. The unprecedented "double doble" at the Olympic long distance events had been done and Viren still had the strenght to achieve a praiseworthy 5th place at the marathon. (4)

|

| Emiel Puttemans and Steve Prefontaine at the 5000m in Munich Olympic Games http://www.elatleta.com http://www.juanjosemartinez.com.mx/ |

As we can see, in Munich and Montreal Moscow

Due to boycott and injuries some of the best long distance runners were not available for the 1980 Olympic Games. It included world cross champion and 10.000m leader of the year Craig Virgin, 5000m European champion Venanzio Ortis, silver medallist in Montreal Carlos Lopes, his compatriot and future record holder Fernando Mamede and the man who had accomplished four world records in 81 days in 1978, the awesome Kenyan Henry Rono. Would the development of the race have been different with them on? Would have change their presence the final results? Maybe but I do not believe it. Anyway it is useless to speculate. The eventual race derived in a spectacular clash between Ethiopia and Finland

Miruts Yifter was back in 1972 an inexperienced athlete on the making, no matter he was already 28 (?) years old. Just the precedent season he had lost to Prefontaine in a competition between Africa and the USA Munich final and now, Mohamed Kedir and Tolossa Kotu had also qualified: every heat in Moscow Moscow Finland

One of the things which made the Moscow Olympic 10.000m final so amazing was the fact Ethiopia Moscow ’s race, Ethiopia

|

| Kaarlo Maaninka, Lasse Viren and Martti Vainio in a local competition http://www.elatleta.com/foro/showthread.php?136398-El-grado-cero./page4 |

In Moscow, Ethiopia had also the best kicker but it was too dangerous to sit in the pack and let the initiative to one man who had proved so good tactically speaking and was intelligent enough to ruin the East African squad chances. It was uncertain if that old Scandinavian man was in the same staggering form than in the previous Olympics but they could not take any risk. Roba Negussie studied thoroughly the circumstances of the race and decided to sacrifice his second best runner, Mohamed Kedir, to make him become a man-trap for Viren. Kedir specially and also his companions executed a flawless strategy to produce an uncomfortable competition for the Finn. Viren liked to run in a fast an even pace so the Ethiopians, always in command, accelerated and decelerated the race continuously to break Viren’s rhythm and at the same time his confidence. The 4th kilometre was done in a very slow 2.57 but the next one was covered in a fast 2.39, to slow down again in the sixth to 2.47. By that point the uneven pace had broken the legs of most the field: Brendan Foster, Vainio, who was having a disappointing performance in Moscow due to overtraining, German Jorg Peter and his compatriot, a young Werner Schildhauer. Mike McLeod, would be soon the next casualty. The leading group had been reduced to five men: Kedir, Yifter, future national coach Kotu and Finns Viren and Maaninka. At that crucial stage, the defending champion tried to take the lead, followed by Maaninka up to three times in the same lap but in every occasion Kedir sprinted to ruin Viren's strategy, overcoming him and then slowing down the race or producing a sudden acceleration, while Yifter would split the two Finns.

|

| Mohamed Kedir leads Filbert Bayi at the Cross Cinque Mulini http://www.elatleta.com |

In Munich Moscow Moscow

Ethiopia ratified its superiority at the time in long distance with successive victories in Cross country, after making its debut in Madrid Moscow Canada Ethiopia

1980 was the last competitive athletic season of Lasse Viren. The only standout Finnish long distance runner left for the next decade was Martti Vainio, who finished second in Los Angeles Olympics after Alberto Cova at the 10.000m. Yet he was later dispossessed of his medal after failing the doping test, due to the use of steroids, in a sad ending for the last generation of flying Finns. No first class long distance runner has come out ofFinland

1980 was the last competitive athletic season of Lasse Viren. The only standout Finnish long distance runner left for the next decade was Martti Vainio, who finished second in Los Angeles Olympics after Alberto Cova at the 10.000m. Yet he was later dispossessed of his medal after failing the doping test, due to the use of steroids, in a sad ending for the last generation of flying Finns. No first class long distance runner has come out of

(1) http://www.iaaf.org/history/OLY/season=2004/eventCode=3201/news/kind=100/newsid=26713.html

(2) http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1092549/1/index.htm

(3) http://www.takethemagicstep.com/ethiopian-wins-with-german-foreign-aid/

(4) http://books.google.es/books?id=O6I-WcoG5egC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Running+with+the+legends&hl=es&sa=X&ei=KI4sT-vzEdODhQfckPj8Bw&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Running%20with%20the%20legends&f=false

(2) http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1092549/1/index.htm

(3) http://www.takethemagicstep.com/ethiopian-wins-with-german-foreign-aid/

(4) http://books.google.es/books?id=O6I-WcoG5egC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Running+with+the+legends&hl=es&sa=X&ei=KI4sT-vzEdODhQfckPj8Bw&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Running%20with%20the%20legends&f=false